In December, Rachel Meginnes’ sewing machine broke. She asked her friend, fellow resident artist Robin Johnston, if she could borrow hers. Nervous about roughing up Robin’s machine by sewing on paint (which is how Rachel broke her own machine), she stopped herself. “I thought about building up texture with more paint instead of by sewing,” she said. “I’m interested in pulling color from the cloth in ways I haven’t before.” From a busted sewing machine, Rachel’s process busted too.

Correction: processes–there are many. Rachel is a relentless pursuer of textures–“texture” having arrived to us from texere in Latin: to weave. Weaving is where Rachel started, and her creation of textures extends from a consideration of fibers, patterns, and their possibilities. How might an artist trained as a weaver accommodate painting methods and material foreign to the loom? Where would that take her? Rachel has gone far, far out with these questions–not unlike the child in the outfield who forgets, the second she looks up and sees all kinds of blue roping through the clouds, about being in a baseball game. Behold the wall of current Rachel Meginnes experiments:

“If they fail, they fail,” says Rachel, about these ideas: gessoed paint build-ups, magazine transfers on cardboard, abraded surfaces, color behaving and misbehaving, thread and weave, articulate paper folds, that ominous X. Looking at each moment of texture, one begins to see the depths of Rachel’s experiments. “What happens when I can’t sand away?” she says, noting one of her techniques. Rachel’s studio time this past winter has involved voicing her internalized methods and then veering away–toward discomfort, change, and not knowing what will happen. As a testament to her endurance in this process, check out her bowl of paint-shocked pins:

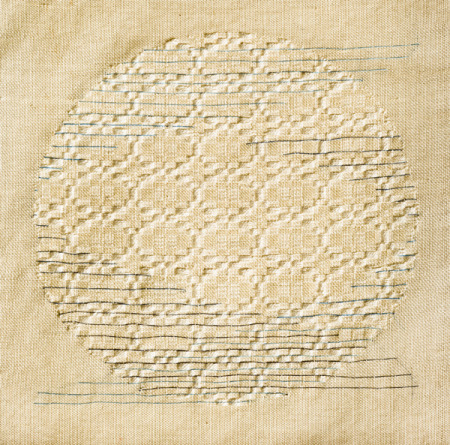

Enduring a winter of self-imposed counter-intuitive experimentation might sound, well, painful. Perhaps the pain, for Rachel, is eased by an adherence to the grid–that endless, giving pattern she uses repeatedly. As I entered her studio, Rachel was applying white strokes of gesso to a fabric made from handwoven scarves that she had bought in bulk, cut up, and then re-pieced. She began to talk about the observational part of her work: watching, day to day, how paint affects not only the surface but the stretch of the fabric. I was immediately reminded of Agnes Martin: how the grid is a constant chance for alteration, for something else to happen. Rachel readily cites Martin, Robert Ryman, and Mark Bradford as influences.

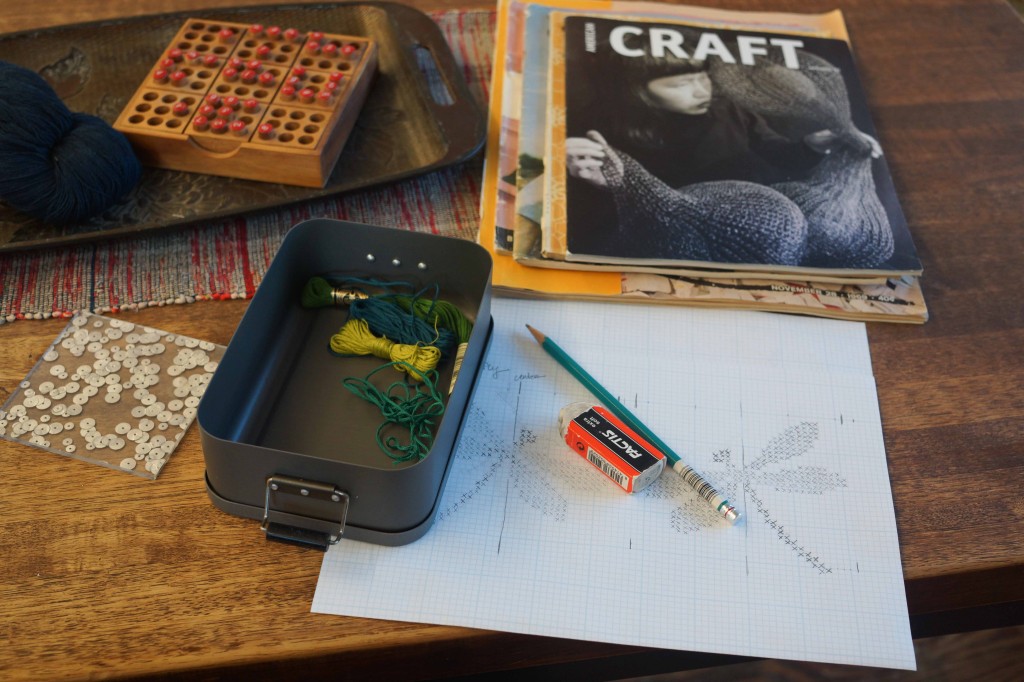

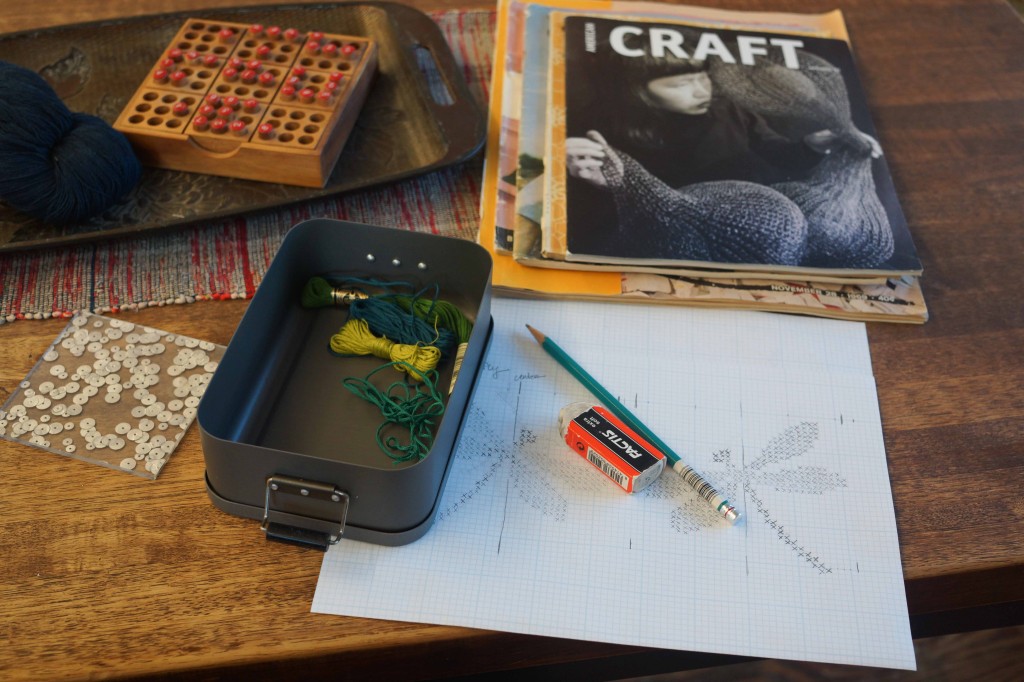

The studio isn’t all action. Set away from a table populated with tubes of paint, there’s a small desk next to a well-tended bookshelf. On the desk, quiet arrangements: a draft for a dragonfly, an old issue of American Craft featuring the image of Ruth Asawa, who said once: “An artist is not special. An artist is an ordinary person who can take ordinary things and make them special.”

Photographs by Robin Dreyer and Elaine Bleakney; writing by Elaine Bleakney

Read Kathryn Gremley’s 2014 essay on Rachel Meginnes’s work from Surface Design Journal here