Penland School of Craft recently unveiled an exciting archival project that will be of use to scholars, historians, and craft enthusiasts for many years to come. The core of the project is the preservation of 250 hours of material contained on at-risk 16mm film and magnetic tape that had accumulated in the school’s Jane Kessler Archives over many years. In addition to several old films, there were audio and video tapes in multiple formats. Included in this material were interviews with Penland artists, instructors, and staff from the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s.

The earliest material is films made by Allen Eaton in the 1940s that present a decidedly dated view of Appalachian culture while documenting traditional craft in Western North Carolina, including early footage of Penland. A film with no soundtrack captures Penland in the 1950s, and a final 16mm film, shot in 1969, highlights Penland’s second director, Bill Brown, glass artist Billy Bernstein, sculptor Don Drumm, potter Byron Temple, and others.

There is also a collection of artist interviews filmed by Chris Felver in 1985 (complete list of interviewees is here) and a series of videos made in the early 2000s by Joe Murphy, a documentary filmmaker and professor at Appalachian State University. These move through Penland’s teaching studios, recording the activities of students and instructors, including demonstrations and lively interviews.

Color film and magnetic media are both subject to deterioration, even if they are not actively used, and Penland’s former archivist, Carey Hedlund, saw the need to catalog all of this material and have it transferred to digital formats. A successful proposal to the National Endowment for the Humanities brought the funds necessary to execute the project, and Penland hired Leila Hamdan, an experienced archivist and collections manager from Memphis, Tennessee as the project archivist.

Leila began work in early 2000, just as the COVID-19 pandemic shut down most of Penland’s normal operations, creating a challenging and isolated work environment for her. She quickly discovered that many of the tapes were not properly labeled or described, making it difficult to identify the contents.

Enter Sallie Fero, a nearby neighbor of the school who had recently retired after 30 years as a Penland employee. Sallie was hired to watch and listen to hours and hours of material with Leila and identify people and subject matter.

Leila selected a vendor to digitize the tapes and films and created metadata for 350 items. She designed and built a data asset management system, a Linux-based content management system hosted on site, and a digital preservation system. She created industry-standard finding aids for individual items and placed all of the files in cloud-based storage. She worked with Penland’s former IT manager Mark Boyd and website designer Jennifer Drum to create the publicly available digital repository.

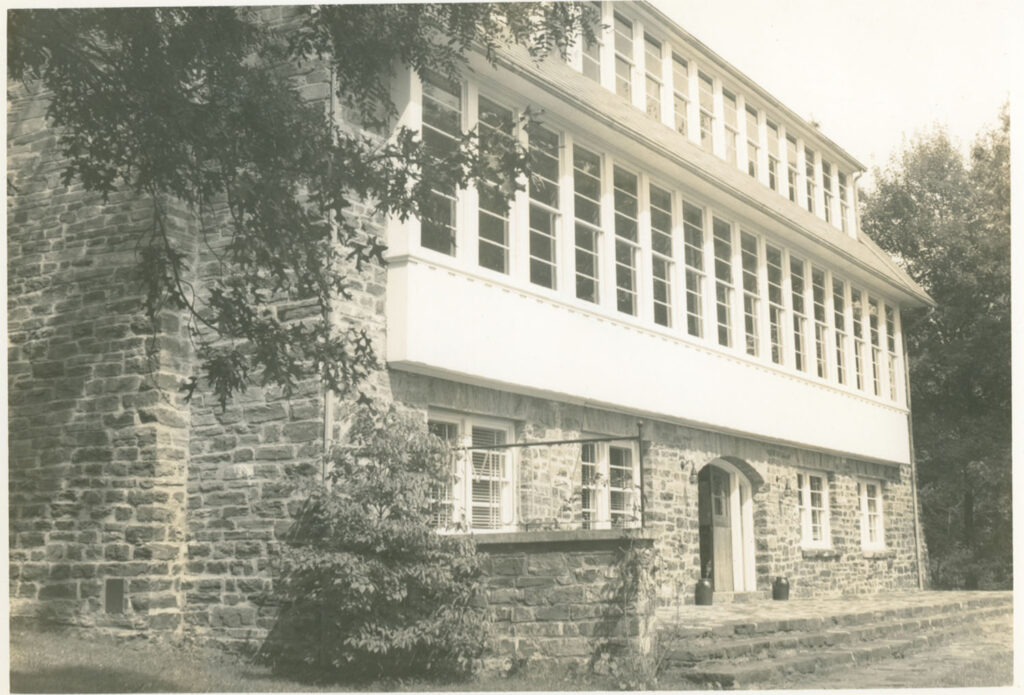

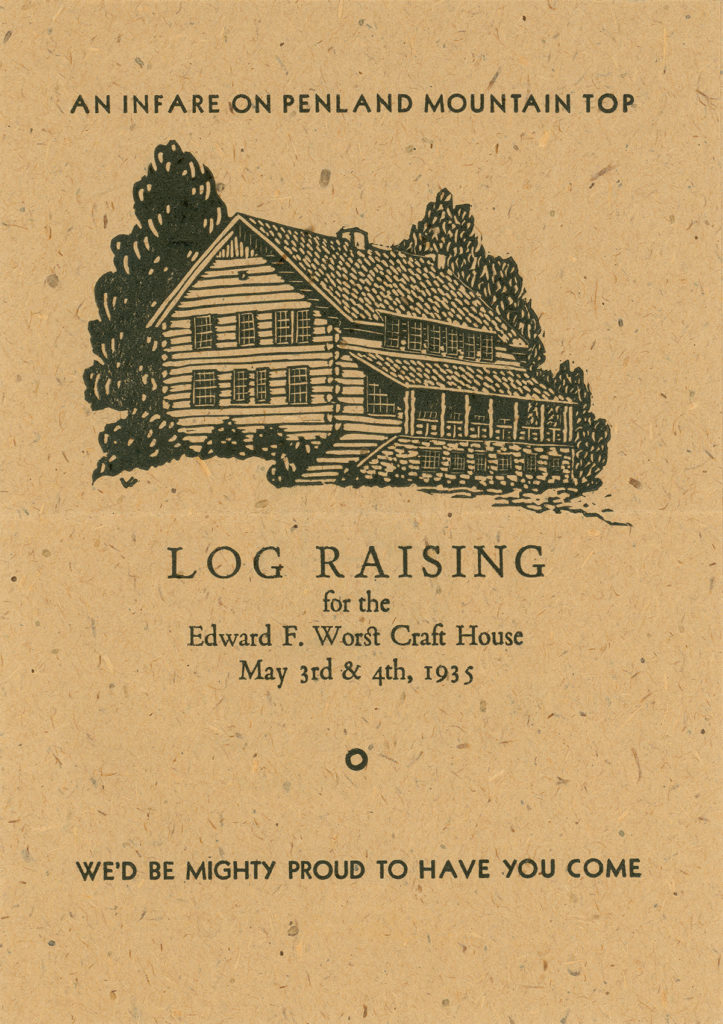

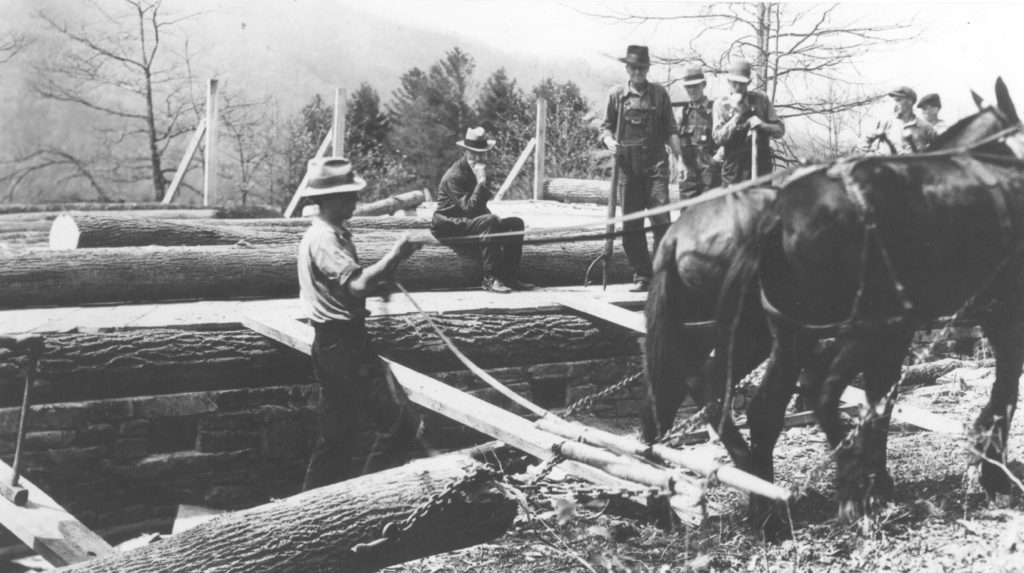

The repository was expanded beyond the films and videos to include a collection of historic photographs of eighteen of Penland’s buildings. Most of these buildings contributed to Penland’s campus being designated as a historic district by the National Register of Historic Places.

During the the two years she worked on the project, Leila also created a Penland Archives Instagram account where she posted a treasure trove of photographs owned by the archives along with a few photographs of objects in the archives.

The digital repository, which is linked from the archives page of the school’s website, currently houses 113 historic photographs and 76 videos ranging in length from a few minutes to more than an hour. These were selected based on their copyright status and streaming permission as well as the relevance of the content. More video and audio may be added in the future, and the complete list of digitized audiovisual material can be viewed by contacting archives@penland.org.

A favorite video of Leila’s is A Penland Story from 1950. “This one was, for me personally, the most impressive to uncover because it brings so many of the old still photos to life and color,” she said. “It has cameos from everyone who was anyone at the school during the time—even Henry Neal cooking in the kitchen, which is remarkable. We see Penland’s founder, Lucy Morgan, in her apartment watching a clown act with friends, work being made in every studio, the list goes on and on.”

We hope you will explore this special resource, and we will continue to highlight parts of the collection on the blog and our social media over the next year.

BONUS: Here’s a video of Harvey Littleton, one of the founders of the Studio Glass Movement, blowing glass in 1985.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom. neh.org

As collections go, the Penland archives are a bit unusual. “There are some archivists who believe that objects have no place in a collection,” Carey explains. “But how would you tell Penland’s story without them?” Indeed, in addition to the many thousands of pages of old publications and photographs and letters, the Penland archives include a rich array of objects, from textiles and pottery to more humorous items like a knit doll of an eccentric woman who worked at Penland years ago. “I’m still seeing things for the first time,” Carey adds. “Whenever I pull a box out and start reading, I find something that’s fascinating or funny or moving. There are real people in those boxes.”

As collections go, the Penland archives are a bit unusual. “There are some archivists who believe that objects have no place in a collection,” Carey explains. “But how would you tell Penland’s story without them?” Indeed, in addition to the many thousands of pages of old publications and photographs and letters, the Penland archives include a rich array of objects, from textiles and pottery to more humorous items like a knit doll of an eccentric woman who worked at Penland years ago. “I’m still seeing things for the first time,” Carey adds. “Whenever I pull a box out and start reading, I find something that’s fascinating or funny or moving. There are real people in those boxes.”