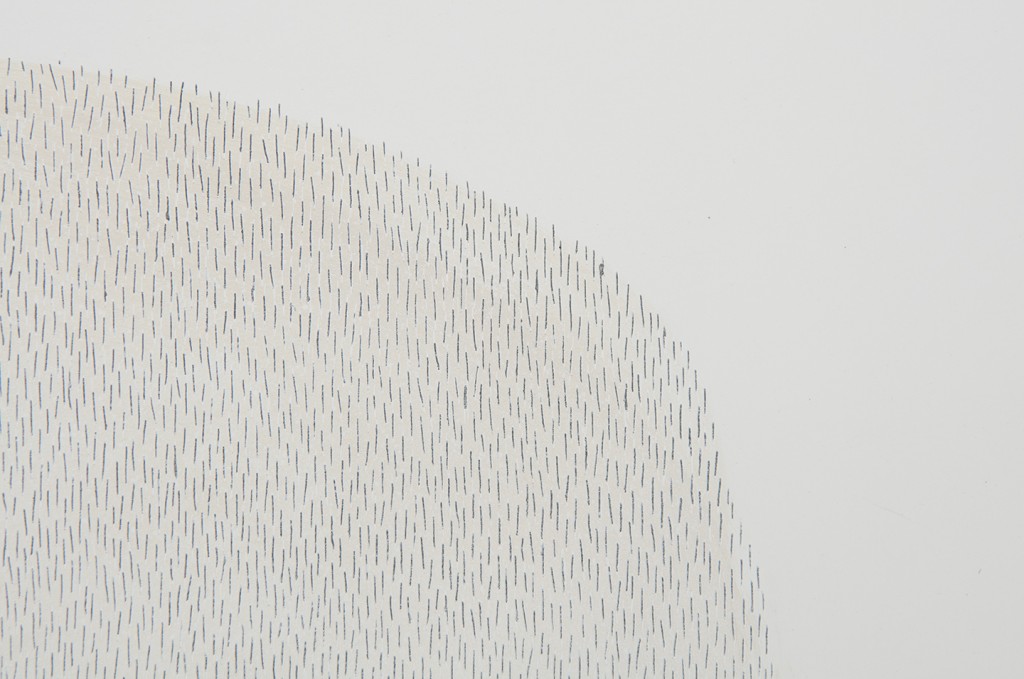

Eleanor Annand, detail from “Isolate,” scribed and abraded drawing on paper (see below for image of the whole work).

An artist goes for a walk in the woods. One foot, and then another. It’s a form of precision. “You walk with a reasonable, natural rhythm; let it be natural, just as with the breath,” says the Buddhist meditation master and scholar Chögyam Trungpa, describing the practice of walking meditation. The artist walks. She observes her weight, her step, its repetition. She looks at the world around her and notices, also, the interior.

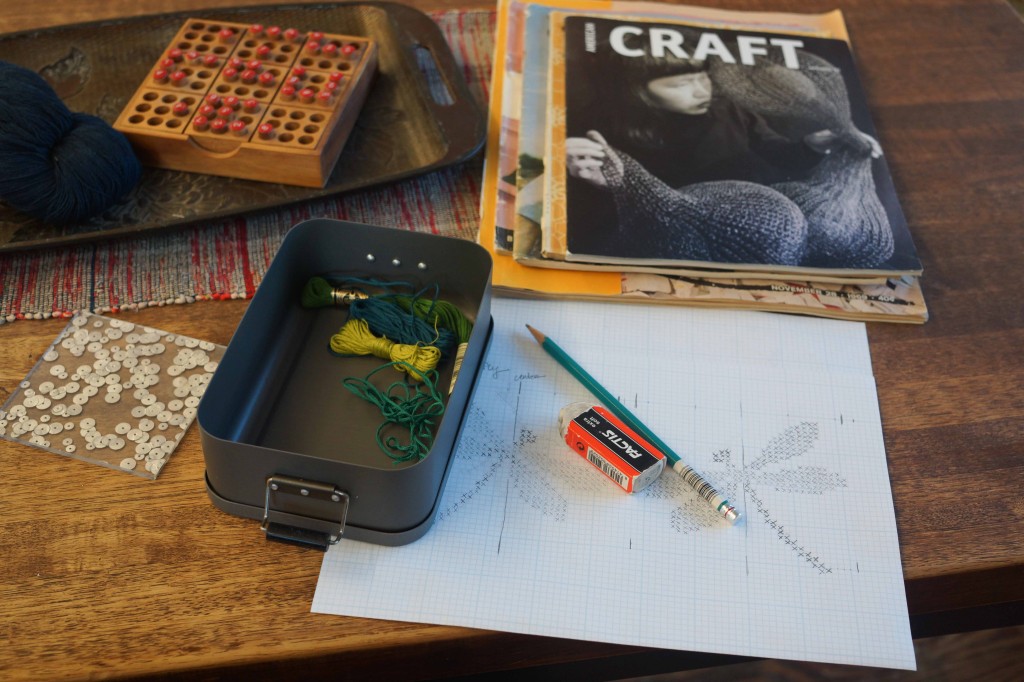

This is one way to think about artist Eleanor Annand’s recent body of work, completed at a time when she was researching meditation and walking—and taking many walks and hikes herself. A former Penland core fellow, Annand now lives in Asheville, North Carolina, and sustains a busy life as a full-time graphic designer. And so, to the dreamy image of an artist walking in the woods, we have to add another image to the story of Annand’s process: the artist wakes up early, goes down to her basement with her tea—and creates before the workday begins. “I don’t binge on creative time,” she says. “I prefer more of a slow and steady approach. A couple of quiet hours in the morning are ideal.”

Annand’s current work, on view until May 11 at the Penland Gallery, is made up of paintings on steel and works on paper. The steel pieces are coated with approximately four layers of enamel spray paint. The paper, coated with ten to twelve layers of paint on top of a layer of gesso. After the coated field is dry, Ele uses a scribe to make her low-relief mark. Marks, we should say—Annand’s works are often tidal surges of mark making (and abraded marks)–a discipline attached to the precise and generative act of seeing that can be experienced in meditation.

Eleanor Annand, “Isolate”

But Annand does not expect you to approach her painting and be enlightened. (Neither does she expect this as an end-result of her own process.) On this point she is clear-eyed. “I see most things in life as grey,” she says, “not black and white. These works aren’t about an incident but about the general emotion I carry from something.” Annand pauses and takes a sip of chai between thoughts. “There is not an answer in my work, but an acceptance. Not a wanting.”

How did Annand, trained in graphic design and letterpress, arrive at this steady point as an artist? Annand took her first workshop—in weaving—at Penland while still in college. Later, after working in graphic design for several years with clients like IBM, Annand took a break from professional life to get back into her hands by taking a fall 2009 workshop in Penland’s print studio. At this point, she applied for and received the two-year Penland core fellowship.

This was 2010. Annand’s first eight-week workshop as a core fellow was with printmaker Phil Sanders. “All of my work was figurative at the time,” she remembers. Sanders would open the workshop with an hour or two for individual drawing time, and he would orbit the room, witnessing. She recalls him pointing to a moment of abstraction in one of her figurative drawings, and saying something to the effect of ‘I think you’re more interested in what’s happening here.’ He was right—Annand’s work has moved, over the years, toward the abstract. “I still won’t commit myself to letting go of the figures,” she says. “I think that they are moving toward a different part of what I make, in illustration.”

To pay attention to what you’re doing—this is the most important thing I learned from Penland, adds Annand. To pay attention leads to true expression. Having a healthy sense of self-awareness has led me to make work I believe is authentic and honest.

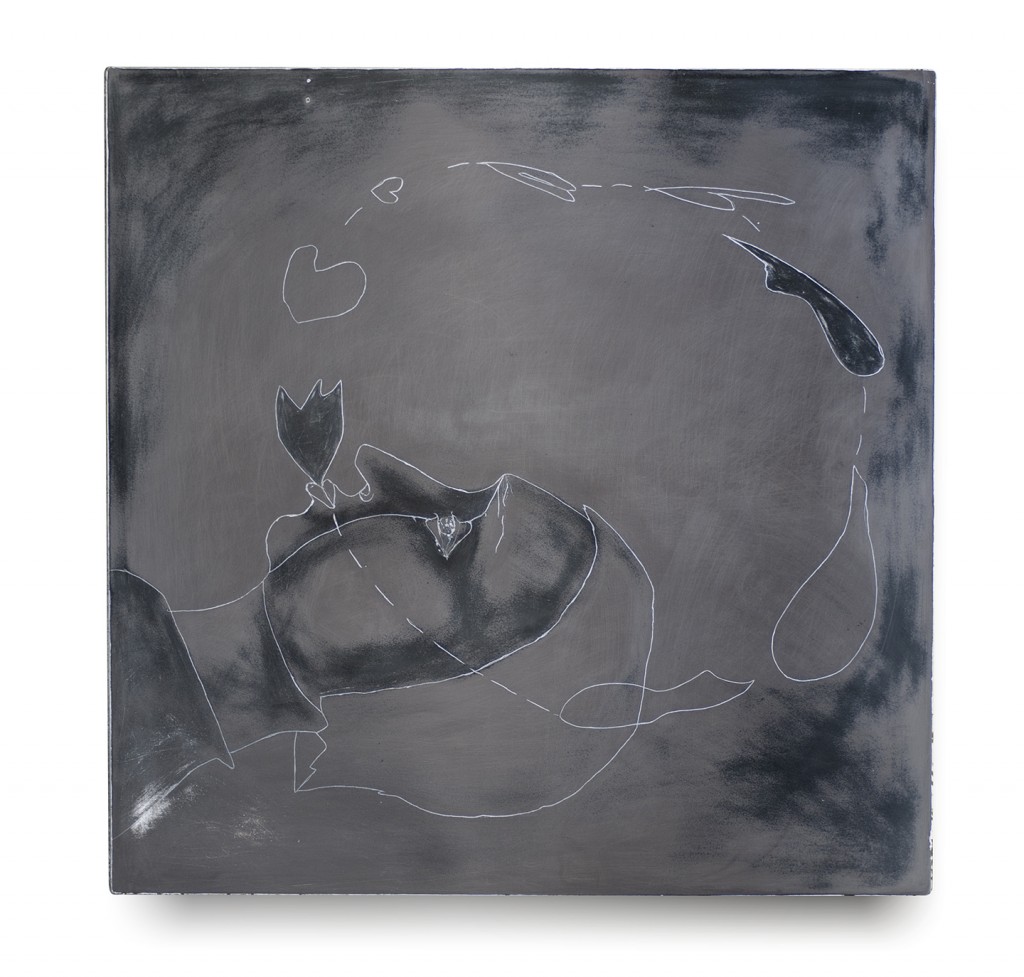

Eleanor Annand, “Pyre,” painting on steel

Our conversation wanders back to walking, how the rhythm of walking sharpens and creates an attention to the rich periphery. She mentions her painting, “Pyre” (above).

“It’s not like I walked into the woods and found a pyre and decided to recreate it,” Annand smiles. “It’s about introspection, and making honest marks. I’m sure that something on my walks, some kind of distraction, helped bring the form inside.”–Elaine Bleakney

Eleanor Annand grew up on the southern tip of the coast of North Carolina. She received her Bachelors of Graphic Design from North Carolina State University where she focused on typography and letterpress. After a range of design and letterpress experience from IBM to Yee-Haw Industries, between North Carolina and Colorado, she landed in the Core Fellowship program at Penland School of Crafts. In the Core program Eleanor investigated printed, drawn, carved, and painted lines on paper, metal and enamel. In 2012 she relocated to Asheville, NC where works as an artist and designer. Her work is on display at Blue Spiral 1 Gallery in Asheville and Light Art + Design in Chapel Hill, NC.

Eleanor Annand grew up on the southern tip of the coast of North Carolina. She received her Bachelors of Graphic Design from North Carolina State University where she focused on typography and letterpress. After a range of design and letterpress experience from IBM to Yee-Haw Industries, between North Carolina and Colorado, she landed in the Core Fellowship program at Penland School of Crafts. In the Core program Eleanor investigated printed, drawn, carved, and painted lines on paper, metal and enamel. In 2012 she relocated to Asheville, NC where works as an artist and designer. Her work is on display at Blue Spiral 1 Gallery in Asheville and Light Art + Design in Chapel Hill, NC.