What possibilities do historic photographic processes offer to contemporary artists? What does it mean to make photographic images with chemically-sensitized and processed materials in the digital era? These are some of the questions raised by “This Is a Photograph: Exploring Contemporary Applications of Photographic Chemistry,” the inaugural exhibition at the newly renovated and expanded Penland Gallery & Visitors Center. Curated by Brooklyn-based photographic artist and long-time Penland instructor Dan Estabrook, the exhibition not only reveals some of the arresting possibilities of these processes, it also brings work by world-class image makers to our community here in Western North Carolina.

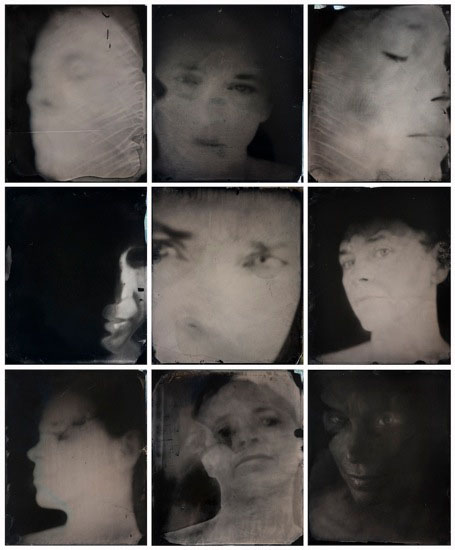

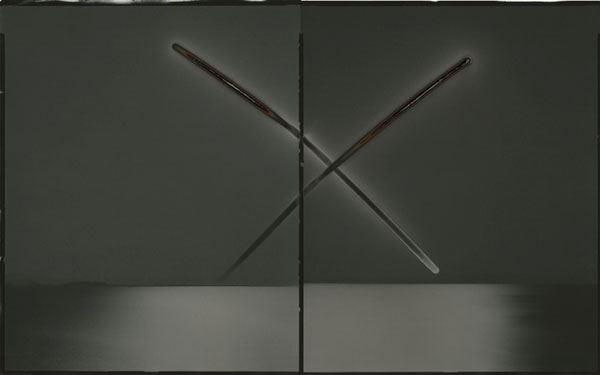

“This Is a Photograph” displays work by twenty-three artists experimenting with a variety of processes and materials in ways that frequently have little to do with their historic antecedents: tintype images made on found metal objects, large daguerreotypes that look almost holographic, images created by painting directly onto photo paper with chemicals, and images made by igniting gunpowder that had been sprinkled directly onto photo paper, to name a few. As Penland Gallery Director Kathryn Gremley describes, “handmade images created through the complex alchemy of light and chemistry are the common ground of the artists invited by Estabrook for this exhibition.”

“This Is a Photograph” opens on March 22, 2016. The gallery will celebrate with a public reception on Saturday, March 26 from 4:30-6:30 p.m at which Dan Estabrook and some of the artists will be present. The exhibition will be on display through May 1.

“This Is a Photograph” features the following artists: David Emitt Adams, Christina Z. Anderson, John Brill, Christopher Colville, Bridget Conn, Danielle Ezzo, Jesseca Ferguson, Alida Fish, Adam Fuss, Mercedes Jelinek, Richard Learoyd, Vera Lutter, Sally Mann, Chris McCaw, Sibylle Peretti, Andreas Rentsch, Holly Roberts, Mariah Robertson, Alison Rossiter, Brea Souders, Jerry Spagnoli, Bettina Speckner, Brian Taylor

Read Dan Estabrook’s essay on the show below, and you can see images of all the work in the show on the Penland Gallery website.

One year ago, I was here at Penland teaching a workshop called “Photography in Reverse,” in which the students and I worked backward through the entire history of photography, stopping at key moments to experiment, play, and think about the nature of each technology. Starting with our smartphones and handheld devices—the very definition of today’s tech—we began to ask ourselves how photography has changed at this critical moment, now that almost all our daily photographic usage is created and printed digitally. At our first step backward in time, with the earliest digital cameras, we learned something crucial: although photography is becoming purely digital, like much else in our life today, we still live in a physical world, and there are artists who will always want to make physical things.

We had to scramble to find the right cords and batteries and software so we could use some early digital cameras from 2001, and it became evident how much harder it was to work with the obsolete technology of 5 or 15 years ago than with the processes of 150 years ago. Most of our computers now can’t run the first version of Photoshop (ca. 1990) or read early Photo CDs or Zip Drives. Even the standard color snapshot is being discontinued, since the machines required to make and develop color films are disappearing for good. The history of photography, like the history of technology in general, seems to suggest that every new system or process is an advancement on the last, making all older forms obsolete. And yet for every technique that has been pronounced dead, there seems to be an artist ready to explore its particular expressive qualities. After all, decades after the invention of mass-produced ceramics, people still want to throw beautiful pots. The artists in this exhibition are each exploring the possibilities of physical and chemical photography to pursue their own contemporary aims, very much in the here and now.

Some are finding a wealth of new beauty in the simplicity of the photographic act—a permanent mark made by the meeting of light and chemistry. Others are deeply engaged with history, in how we look backward from the present or forward to the years ahead. Still others have realized how much can be revealed in the life of a physical photographic object. Any technology that can still be used by artists, whether it’s something that can be handmade or something produced from saved and scavenged machines, is going to have an ongoing parallel history through the work of these artists, not just as a period relic but as a technology carried along into the present with new developments and new meaning for the future.

A decade from now it will likely be easier to make a daguerreotype than to use the iPhone you bought in 2016; in 100 years that will be even more true. In the meantime, there will be artists like these to involve us in the material world in which we live, and to expand the possibilities of just what a photograph is.

Dan Estabrook | Studio Artist | Penland Instructor