This is Penland resident artist Dean Allison beginning the process of creating a mold from the head and shoulders of 10-year-old James Haley. The mold will be used in the creation of one of Dean’s mesmerizing cast-glass portraits. James’s mother, Penland program director Leslie Noell, was close at hand to coach him through the 45-minute process. James got to pick the soundtrack, so Hamilton was playing throughout.

The first step was to coat James’s hair with cold cream. Then Dean began to carefully cover his face with a silicone rubber that starts to set up in about about 10 minutes. He used his fingers to make sure all the details of James’s face would be well molded. He also took care to maintain breathing holes for James’s nose.

With his whole head and shoulders covered, James began to acquire a Halloween-enviable, Creature from the Black Lagoon look. At this point it was important for him to sit very still as the material began to set up. “Pretend you are thinking about the hardest math problem you’ve ever had to do,” Dean instructed.

The next step was to create a two-part plaster shell that will be used to keep the flexible mold rigid later when filling it with hot wax. Dean and his assistant Sarah Beth Post formed the shell using the same kind of cloth/plaster strips that are used to make a cast for a broken bone.

Once both halves of the shell were complete, they were left briefly to harden and then were carefully removed.

Here’s the front half of the shell coming off.

Dean carefully slit the mold up the back while Sarah Beth separated the rubber from the shirt.

And with Mom’s assistance, the mold was removed as gently as possible.

There it goes.

And James emerged intact!

“I was thinking about bagels the whole time,” he said to Leslie, “so now we need to go get a bagel.”

Hmm…well played.

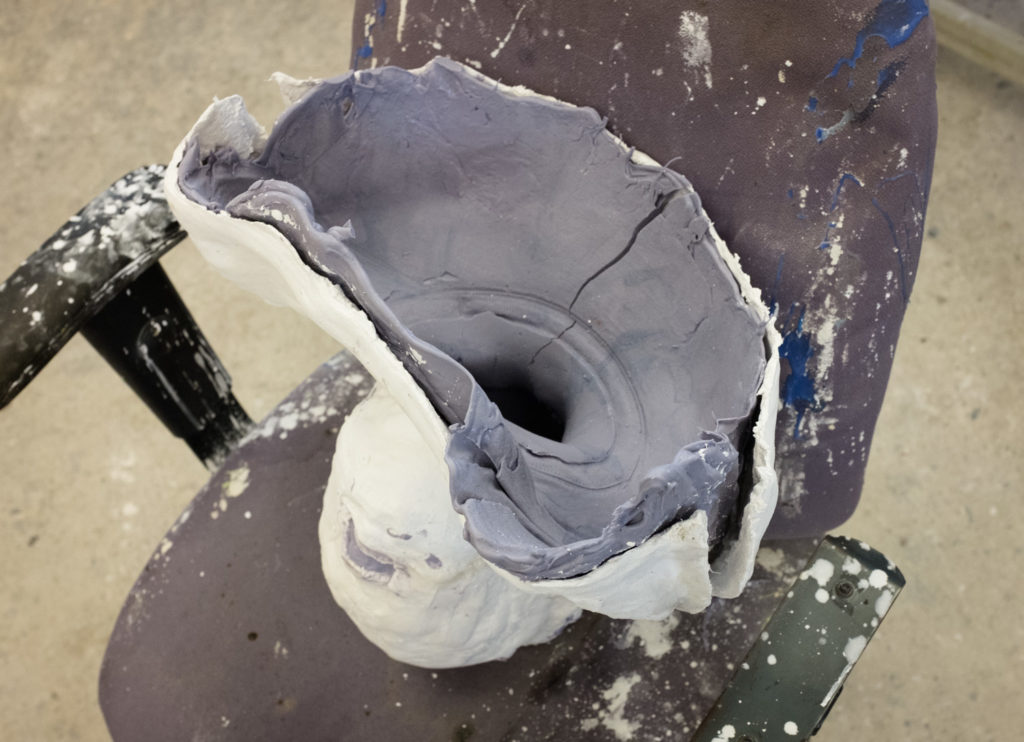

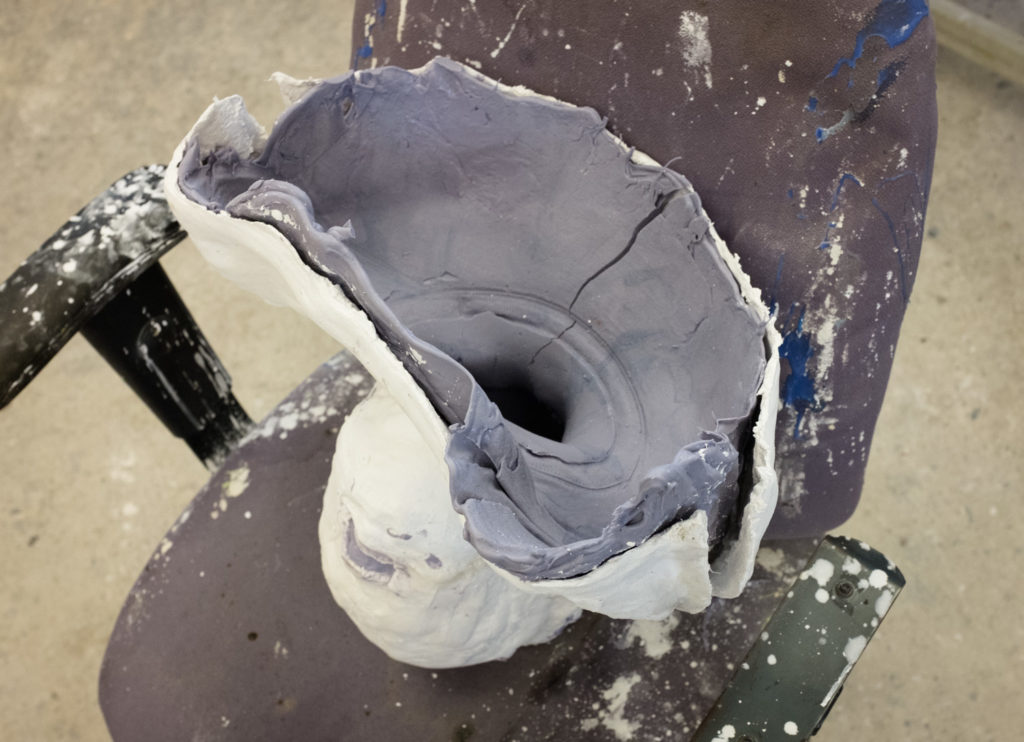

This process is just Dean’s first step. Here’s the rubber mold back inside the plaster cast (upside down on the chair). The next step is to fill it with hot wax to make a wax positive.

Here is the wax model of James. Dean will clean this up quite a bit and do some additional sculpting—particularly on the hair.

He will use this wax model to create a new mold made of reinforced plaster, which will retain all the detail that’s in the wax. Finally he will melt out the wax and fill the plaster mold with molten glass to create the glass sculpture. After the glass cools Dean will put in hours of polishing and cold work to refine the piece before it will be ready for mounting.

Before joining the Penland residency, Dean Allison was Penland’s glass studio coordinator. He has a Masters of Art in Visual Art from Australian National University. His work has been exhibited recently at the National Portrait Gallery in DC, SOFA Chicago, and Blue Spiral I in Asheville, NC. You can see many examples of his portraiture on his website.