CONVERSATION | Pneuma

Christopher Colville + Maggie Jaszczak

October 2 – November 18

CONVERSATION | Pneuma

Christopher Colville | Bio

Christopher Colville | CV

Christopher Colville Website

Maggie Jaszczak | Bio

Maggie Jaszczak | CV

Maggie Jaszczak Website

For more information or to purchase works in the exhibition please contact Kathryn Gremley at gallerydirector@penland.org or 828.765.6211

Wring Out My Clothes

Such love does

the sky now pour,

that whenever I stand in a field,

I have to wring out the light

When I get

home.

– St. Francis of Assisi

“Don’t think about what you’ve left behind” The alchemist said to the boy as they began to ride across the sands of the desert. “If what one finds is made of pure matter, it will never spoil. And one can always come back. If what you had found was only a moment of light, like the explosion of a star, you would find nothing on your return.”

? Paulo Coelho, The Alchemist

MAGGIE JASZCZAK

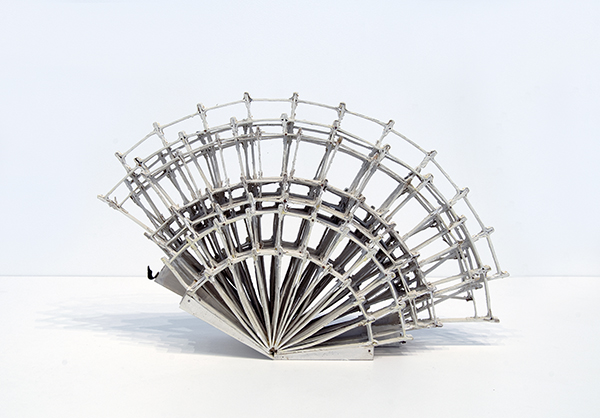

I work with wood, textiles, hair and bone, to make everyday objects. From baskets, brooms and brushes to bedding and chairs, I am drawn to these quiet everyday forms, adhering to the Shaker belief that ‘beauty rests in utility’.

I develop my work according to minimalism of form and honesty of material and process. Particularly I am drawn to the muted, minimal textures and colors of leather, linen, wood, bone and hair. I rely on the natural processes of these materials – mildewing fabric, shrinking leather, cracking or flawed wood, the bleeding of metal around a nail hole – for the decorative elements in my work.

My aesthetic draws from my cultural lineage, blending together basic, hand-made, almost crudely functional forms in the pioneering spirit of North America – bread bowls, troughs and baskets – with the simple clean lines and minimalism of Northern Europe, and the odd, small homage to the textile arts of Britain’s Romantic past.

CHRISTOPHER COLVILLE

The Ouroboros or snake that swallowed its tail is an ancient alchemist’s symbol representing the eternal return. As a serpent devours its tail it completes the cycle of birth and death, finding nourishment through its own flesh, illustrating the dual nature of creation and destruction.

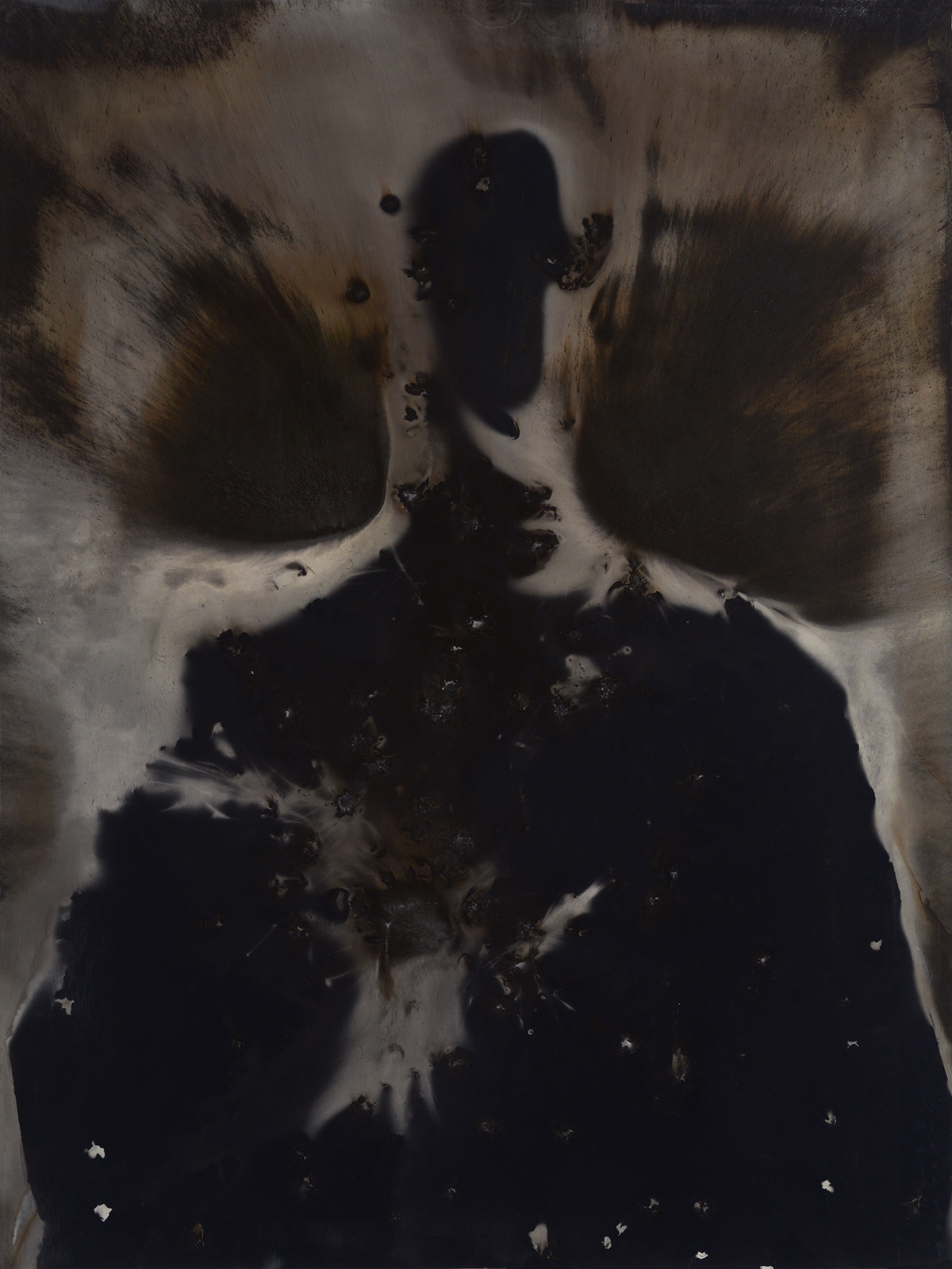

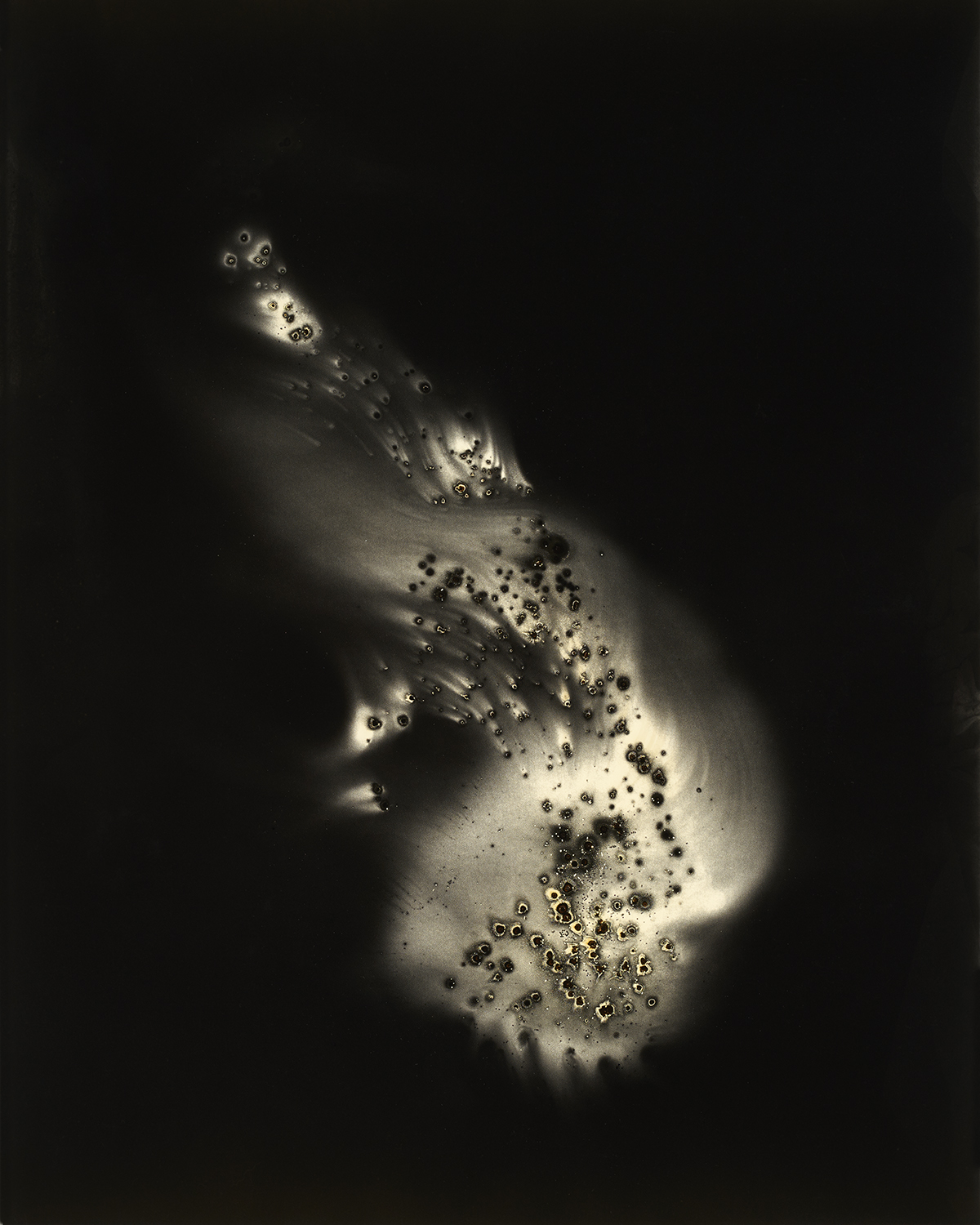

The Ouroboros variants are a meditation on the duality of destruction and the infinite possibilities of return. The prints are made using black powder, an explosive compound discovered by alchemists in their quest to create the elixir of life, a formula that would grant immortality and the ability to transmute one material into another. Black powder was not an elixir but instead a powerful weapon of control and destruction.

To create these images black powder is ignited on the surface of silver gelatin paper. I control the blast using a continuous sharp band of steel coiling around on itself repeatedly like the devouring snake. The ignition of the powder pushes sparks, light and heat through the channels of coiled metal as the destructive flash escapes transforming the silver, scaring papers, birthing a beautiful record of a violent event in the form of an Ouroboros. Inside the coiled body traces of constellations appear. The patterns of stars are residue of fire pushing through voids in a steel disc I perforated with a map of the night sky to create my first variants.

On a personal level the Ouroboros prints offer a counter point to more aggressive imagery I have been pursuing. I am committed to this difficult, aggressive work that engages the volatility of contemporary American culture but feel a personal need to balance the dark images with something that promises light and introspection. Early Egyptian representations of the Ouroboros depicted the serpent as half black, half white creating a duality or harmony similar to the Taoist Yin Yang. These images are part of my own balancing act, a place that offers a centered return.

Exhibition Essay | CHRISTOPHER COLVILLE

Jennifer Colville: I’m curious about your process. I know you often go deep into the Sonoran Desert scavenging for discarded shooting targets, remnants of other people’s violence, sport, or private rage. You then wait until night, place the targets on gelatin silver paper, and ignite gunpowder on their surface. The explosion imprints the negative form of the target, while fire burns through the bullet holes, pitting and scarring the paper in miniature constellations. I love how the targets become a medium to channel images that appear so serene. To me they recall blots of light behind closed eyelids, aerial views of natural erosions. Even the images of torsos with visible bullet holes evoke calm distance, as if we’re hovering over or seeing them through a dream. Could you say more about your work as ritual to transform violence into art?

Christopher Colville: This work is driven by ritual. In college I studied both anthropology and art but recognized creative roles better suited my temperament. Artwork provided an outlet for my desire to participate in the creation of mythologies. After orchestrating these nighttime interventions, the work seems very much like reading tea leaves at the bottom of a cup where I hope to find something surprising and beautiful transformed from the artifacts of violence.

JC: When I see you work and hear about your process I can’t help but think of us as children smashing caps full of gunpowder. I’m thinking of that childhood pleasure in violence and staged danger—smashing things, making small explosions, rigging up a risky but not too risky thrill. Do you think your work speaks to our innate violent compulsions, yet offers an enactment of how they might be channeled into something productive? I’m thinking about the danger that comes with making these images, the thrill of the risk involved in working alone at night in the desert, and with explosives.

CC: Making the prints is a strange solitary performance. I am aware of the absurdity of my actions but also revel in the subversive act. For all of the serious art/photo theory that I believe the work engages, the pleasure of risk and the thrill of pushing limits is at its the core. I have a vivid memory of childhood—the freedom we had to run wild, challenging each other but also time spent in solitude, testing every boundary in an attempt to understand the world.

J: I wonder how you think about this process in relation to your two young sons. Do they ever watch you work?

C: Wyatt and Oliver love watching the work. They often watch from their bedroom window after going to bed as I make small explosions in the backyard. Like good accomplices they egg me on to make slightly larger and more dramatic explosions. They are also two of my best critiques, giving honest, thoughtful feedback.

JC: I remember you writing a while back about our dad, a moment of bonding that involved firing a gun.

CC: That was New Year’s Eve, 1983. Papa wanted to celebrate the new year with a bang. He cut the birdshot out of a shotgun shell, rendering it harmless, and we took it into the back yard. I was proud to be a conspirator in this diversion from his normally reserved and quiet nature. At midnight he pointed his gun to the sky and pulled the trigger. To our surprise, the barrel emitted a small swirl of sparks, and an impotent poof of smoke that was more of a whistle than a bang. The unexpectedly muffled explosion left us standing, dumbfounded, until Papa looked to me with an amused smile and said, “Well that was something.” It is one of my favorite memories.

Essay-interview by Jennifer Colville, writer and educator

Jennifer Colville is the founding editor of PromptPress, an online and book arts journal for the interplay of visual art and writing (promptpress.org). Her collection of short stories “Elegies for Uncanny Girls” was published by Indiana University Press in 2017. She holds a Ph.D. in English and Creative Writing from the University of Utah.

Exhibition Essay | MAGGIE JASZCZAK

A friend has been posing a question: “If I could give you the answer to any question, what would your question be?” When I tell this to a colleague, a researcher who studies the calling of vocation, he says, “But, of course, everyone would ask the same question, some version of, at the end, what does it all mean?” My husband strongly objects. For him, it’s proceeding in the face of not knowing that is the nobility of our human endeavor. The brother of the friend who posed the question, by the way, would ask for the numbers to win this week’s Powerball.

Our most elemental human dilemmas, both physical and existential, are inscribed in Maggie Jaszczak’s work. Her objects, like my friend’s question, invite us to reflect on the nature of our existence. Her methods – basketry, leatherwork, tooling – hark back to our earliest technologies. Her materials – bone, skin, hair – are also ancient, the materials of which we ourselves are made, as susceptible as we are to time and decay. Her objects can be mistaken for artifacts, perhaps because the questions she is addressing are the questions that have been ours since the beginning of time. How do we collect what we need to sustain ourselves? How do we protect our vulnerable bodies? How do we thrive in the face of death and all its weaker incarnations – threat, uncertainty, change, loss, departure?

The mystery & the eeriness that surrounds Maggie’s objects is that they do so much more than the artifacts they resemble: hovering around each of them, as both a presence and an absence, is a palpable sense of some intangible consciousness. In the urgency & immediacy of their making, in their primal utility, we sense some being, mortal or other worldly, removed in time from us perhaps by millennia, preoccupied with survival, with a more salient awareness than ours of forces seen and unseen, a being that makes our own existential dread more vivid.

Buddhist thought describes a space – storehouse consciousness – where everything that humans have ever experienced, everything we have ever forgotten, is collected. Maggie’s power as an artist is that with an economy of means she puts us in touch with something like that space, an encompassing consciousness of who we are at our most essential. Her work proffers connectedness, that our individual questions are also our collective question. Even as she makes us aware of our mortality, thru the attentiveness and reverence of her making, she reminds us of humankinds’ resilience and ingenuity, the nobility of our efforts in the face of the dark verities.

Essay by Christina Shmigel, artist and educator

Christina Shmigel is a contemporary sculptor, studio artist, educator, and former Penland resident artist. Christina’s sculptures include traditional materials such as steel, wood, and paint, but also may include bright plastic pinwheels,cardboard, plumbing parts, and found furniture. Her BFA from RISD is in painting, and she followed it with an MFA from Brooklyn College that she describes as “more conceptual.” Later, she returned to school for a second MFA at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, this time with an emphasis on technical skills like blacksmithing and casting. Recent exhibitions include Ukranian Museum (NYC), Duolun Museum of Art (Shanghai), Laumeier Sculpture Park (St. Louis), St. Louis Art Museum.