Jack Mackie does not identify as a glass artist, nor has he studied the art of blowing glass. But this January, he came to Penland for a week of winter residency in the hot glass studio with some big ideas. “I’m a public artist,” he explains. “The project is the medium, and I make the framework.”

The project that brought him to Penland is the Burnsville Gateway, a public art installation planned for the nearby town of Burnsville, NC as part of the North Carolina Arts Council’s SmART Initiative. The initiative aims to use art to build stronger communities and economies, and those goals have been at the forefront of Jack’s mind throughout the design phase. “There’s a deep tradition of craft here, of quilts, of weaving, of pottery, of baskets, and of glass,” he explains. “One of the things that I wanted to help illuminate through this project is the community of glass that is here, to give prominence to something so special about the area that is not always visible.”

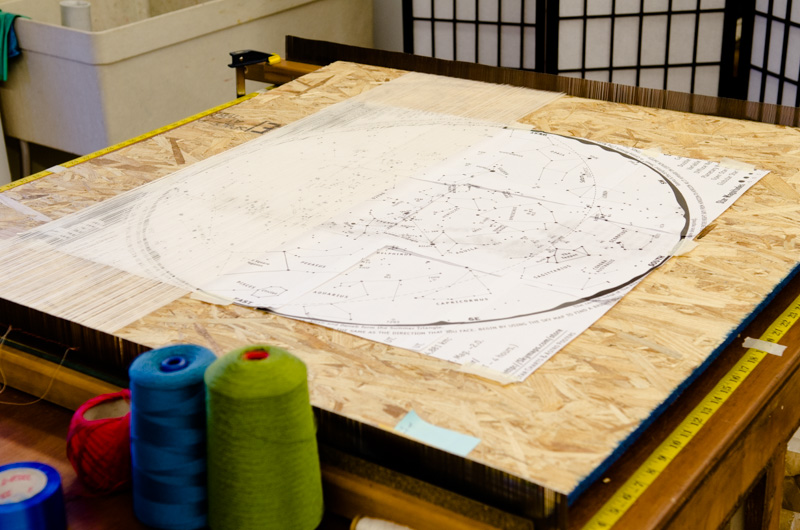

To that end, Jack brought a team of skilled local glass artists with him to Penland: Courtney Dodd, Rob Levin, Kenny Pieper, Dave Wilson, and Hayden Wilson. Together, they worked to create the first glass prototypes for the Burnsville installation, filling the studio with between 800 and 1000 blown-glass pieces in the course of a week. “This artwork is being made by the people who live here,” Jack states. “I simply am providing—conceptually and literally—the frame that their glass artwork is going into.”

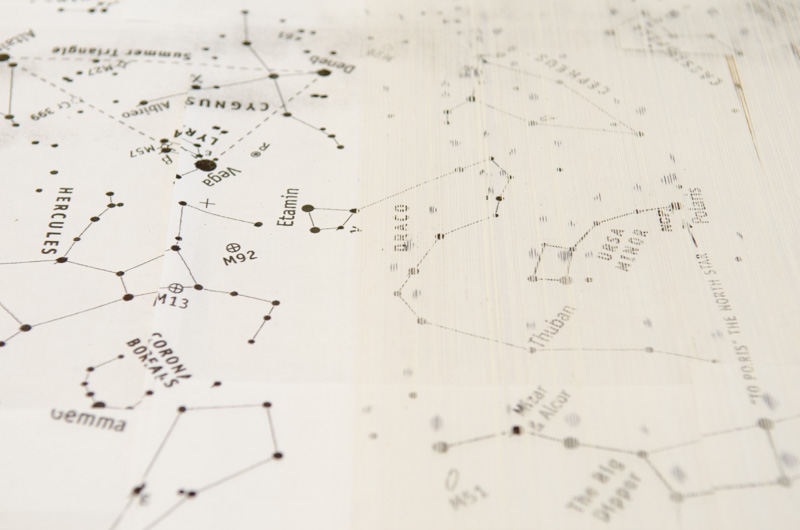

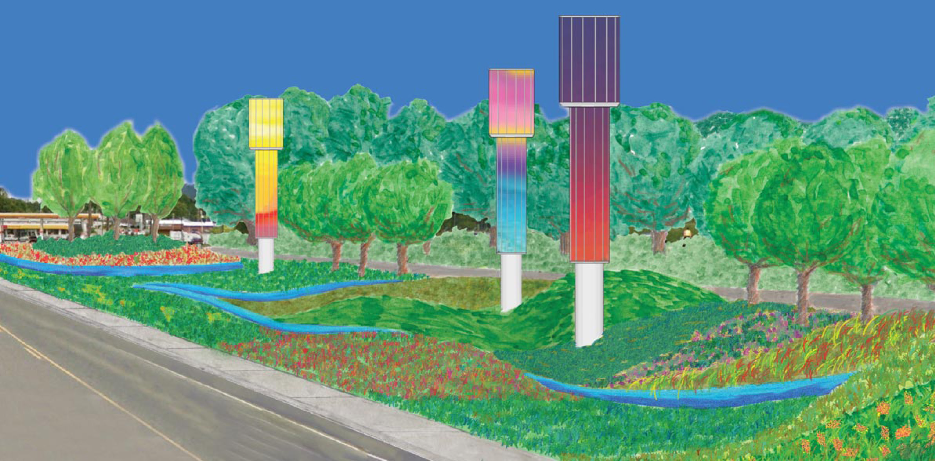

Jack’s vision for Burnsville is expansive and draws on the town’s artistic heritage, mountains, history, and designation as one of only a handful of “Dark Sky” communities in the country. At the center of his plans is the telescope, which he connects both to the town’s past (Burnsville’s founder, Otway Burns, was a naval hero who used a telescope in navigation) and its future (a large public telescope and observatory is being planned for the nearby Star Park). The central feature of Jack’s installation will be six giant “telescopes”—towering columns of illuminated metal and glass that stand at the entrances to the town, three on each side, viewable from the highway as visitors crest the hill.

It was these telescopes that the team focused on during their week at Penland. Each one measures between twenty-four and thirty feet tall and features “baskets” of blown glass orbs held in by a sturdy wire mesh. At first, Jack envisioned each telescope as a different color, but a sunset one evening changed his mind. “I was driving, and I looked in my rearview mirror,” he tells me. “I saw the colors of the sunset and I thought, ‘That’s it!’” Now, the telescopes on the east entrance to town feature gradations of the yellows and pinks of sunrise, while the western telescopes boast the intense oranges and purples of early evening. From a distance, the reflective rainbow effect of all that glass is quite stunning. “It’s so much more than my color sketches,” Jack comments. “It’s light moving through color held in the medium of glass.”

Up close, the telescopes maintain their power to draw the viewer in. Rather than simply creating smooth, hollow globes, Jack’s team of glass artists created richly-textured shapes—some are ridged and round, while others are curved and spiraling or bulbous or decorated with diamond patterns or delicate bubbles beneath the surface. “I like that each one is different, that they’re tactile and engaging, that people can reach in and experience the glass,” Jack says. “In a society where more and more things are built uniformly and built by the billions, to have these handmade pieces as part of our civic public infrastructure was very attractive to me.”

Over the next couple months, Jack and his team will be busy fabricating hundreds more glass orbs for the project, which will likely involve at least one more trip to Penland and possibly the participation of a few other local glass artists. “We couldn’t make this happen without the vision and ability of these artists and a place like Penland for people to come together to work,” Jack notes. “I want to give these artists ownership of the project and at the same time funnel money into the local community through their work.”

The Burnsville Gateway—complete with the six telescope columns, as well as artistic benches, walkways, and other streetscape elements—is set to be installed sometime in the second half of 2017. When it is finished, it will be a testament to the creativity, skill, and vitality of the Burnsville community and the artists who built it piece by piece. “That’s one of the things that public art can do,” Jack concludes. “It can make a place unique, draw out its special qualities, and illuminate them. In our case, it will literally illuminate the quality of the work and the lives that are here.”

For more information on the project, the process, and the artists behind it, we highly recommend watching these two videos by local videographer Chanse Simpson.

Part 1: Telescope Gateways into Burnsville, NC

Part 2: Telescope Gateways into Burnsville, NC