“Do something. Start with pleasure. Make a list of all the things that are pleasurable in your life and then make an art form out of one of them. And if you’re courageous, make a list of all the things that are difficult in your life and make an art form out of one of them.” -Paulus Berensohn, speaking in the film To Spring from the Hand

On the afternoon of Sunday, June 18, 2017, a group of friends gathered at the Carolina Memorial Sanctuary, a green burial site near Asheville, North Carolina, to say a final farewell to artist and teacher Paulus Berensohn. In a clearing on the wooded site, a grave had been hand-dug by Jonah Stanford who, when he was a teenager, was the first of several dozen young people to adopt Paulus as “fairy godfather.” A small crowd waited by the grave and then, through the woods came the sound of a fiddle and an accordion leading a group who were bearing Paulus’s blanket-wrapped body in a sling while several more people carried a cardboard coffin that had been completely covered, by Paulus and a number of his friends, with a collage of drawings, pictures, paper, and poems.

The body and the box were laid gently on the ground. Paulus’s friend Debra Fraiser welcomed everyone, and then someone rang a little bell, which was the bell from the screen door of Paulus’s house, just down the road from Penland School. Every day at 5:00 PM, Paulus welcomed visitors for “Splash,” which meant engaging conversation and a small glass of scotch mixed with fruit juice. Debra explained that some of Paulus’s most frequent visitors would be speaking, each of them introduced by the bell. This led to twenty minutes or so filled mostly with the reading of poems.

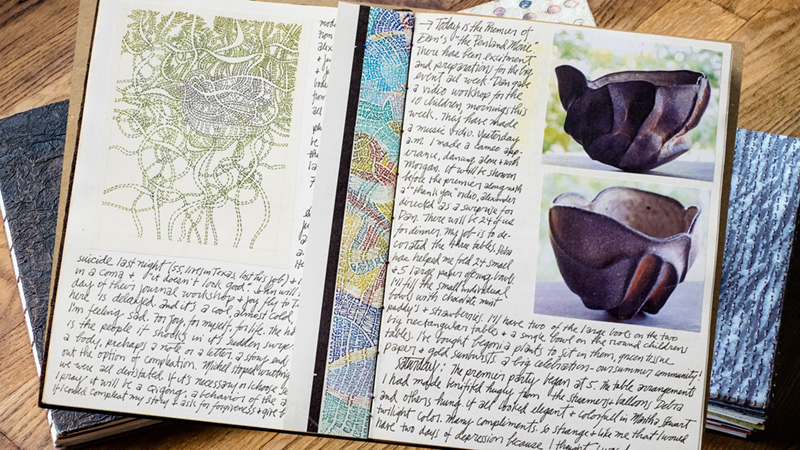

Paulus was a great lover of poetry. He had many poems memorized and enjoyed reciting them (often with a bit of embellishment) in his soft, slightly-smoky voice accompanied by expansive gestures with his hands and arms that left no doubt that he was and would always be a dancer. He had beautiful handwriting and often copied poems into the handmade, Coptic-bound journals that were an integral part of his wide-ranging artistic practice. Although he was made famous by his book Finding One’s Way with Clay, and he was a beloved teacher of clay workshops, for many years he had also taught workshops in the making and keeping of journals. To encourage the practice of copying poems, he would dictate them while his students wrote them into their own books.

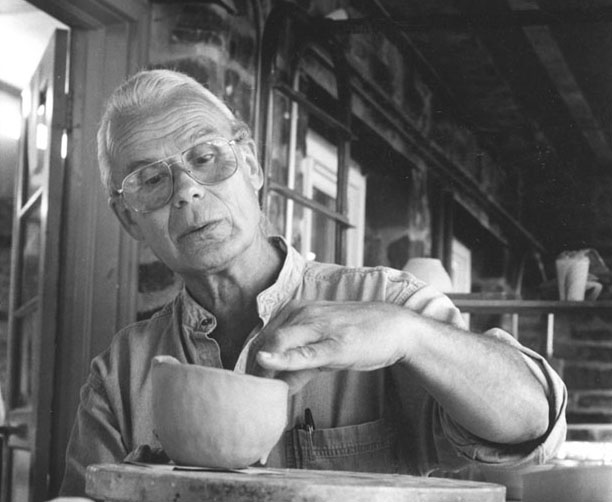

Paulus grew up with a desire to dance, and as a young man he studied at Julliard and Bennington, trained with Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham, and then danced professionally in New York City. But then at a gathering outside of the city he saw the potter Karen Karnes working in her studio. “It had a big window. I stood there and watched Karen from the back, sitting on her old Italian kick wheel,” he said in a 2009 interview. “The first thing I saw her do was to pull up a cylinder of clay and at the same time lengthen her spine. And then—this was what got me—she reached for her sponge in the slip bucket, picked up the sponge, without taking her eyes off the cylinder, and squeezed some slip onto her work. The gesture of sightlessly reaching with her hand was elegant and inevitable. I thought, that’s a dance to learn.”

Through Karnes, he met M.C. Richards and followed her to a pottery workshop she was teaching at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine. He fell in love with clay, and left the world of professional dance behind him, although dancing continued to be part of his daily life. He began teaching pottery almost immediately, and in 1969 one of his fellow Haystack students, Cynthia Bringle, invited him to teach a workshop with her at Penland. Around this same time, he had started experimenting with pinching and other handbuilding techniques. In deference to Cynthia’s great skill at the wheel, he taught pinching in their workshop and that technique came to define his relationship with clay.

Bill Brown, Penland’s director at the time, invited Paulus to return as a teacher and then to stay for a one-year residency. During that year he wrote a long letter to his former students at the Wallingford Potters Guild about pinching and the use of colored clay. This text became the basis for the book Finding One’s Way with Clay, one of the most influential craft books of the 20th century. In addition to detailed instructions and photographs by True Kelly (who still lives near Penland), it includes descriptions of his teaching exercises and suggests a meditative, introspective approach to making. First published in 1972, it is still in print.

Paulus became a great teacher of workshops, and through them he touched thousands of lives. He taught at Penland and Haystack and other venues in the U.S., the U.K, and Australia. He also spoke to dozens of groups in workshops taught by his friends. In his teaching and in his life, he came to embody a few strong messages: that creative work, or “behaving artistically” as he often put it, has an intrinsic value to the maker and to the world; that art need not be connected with commerce; and that the “craft arts” (again, his term), because of their connection to primary materials, can help to heal the earth.

In recognition of his teaching, he was made an honorary fellow of the American Craft Council, he was given an honorary membership in the National Council on Education in the Ceramic Arts (NCECA), he received a Distinguished Educator’s Award from the James Renwick Alliance, and he was Penland’s 2016 Outstanding Artist Educator.

Sometime in the 1980s he settled near Penland School and lived there until his death. He loved the school, which he once referred to as “a kind of monastery on behalf of the human hand.” He taught workshops regularly and for several years he served as the school’s program director. He often spoke and recited poetry at the gatherings that open each Penland session. Although he did not sell his work, he gave it generously to the Penland auctions (and to the auctions of other organizations). He was an informal advisor to several Penland directors, and, through his close friend and student Meg Peterson, he was a great influence on the programs Penland runs in the local school system, many of which involve handmade journals. He was an active supporter of various community groups. He nurtured and encouraged young artists and the children of many of his friends. And he welcomed scores of those friends to his door.

Over the years his artwork expanded to include drawings, needlework, paste paper painting, monoprinting, cut and woven photographs, and, of course, his marvelous journals. He felt that mending should be an art form, and his beautiful thrift store clothes were often enhanced with carefully stitched patches. Although he had a well-known suspicion of electronic technology, he loved the color printer, which he used in producing the cards he sent by the hundreds on Valentine’s Day and the solstice (which he liked to call “soulstice”).

Paulus died on June 16 in a hospice facility in Asheville about a week after he had a major stroke. His health has been steadily declining and a group of close friends had been keeping an eye on him and taking care of his food and other needs. Nevertheless, he continued to have visitors and to show up at community gatherings, gallery openings, and the Penland coffee shop. Nobody who saw him in the month before his death or who sat with his body after he died failed to notice that his ponytail had given way to a short haircut and that his white hair was mostly dyed bright blue.

After the graveside poetry was finished, Paulus’s friends gently placed his body in the cardboard casket and lowered it into the ground. People took turns tossing a little dirt into the grave, which then gave way to shoveling until they had made a mulch-covered mound under the trees.

In addition to introducing each of the speakers that afternoon, Debra Frasier said a few words of her own about the meaning of Paulus’s life—and about that blue hair. She had been listening to the book Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond, which says that wild barley and flax had a seed pod that burst in order to spread its seed as widely as possible. The domestication process involved collecting and replanting the few seed pods that did not burst—the tame ones. Then Debra explained that a month before his death, Paulus cut his hair short and asked to have it dyed blue because, he said, “I want to look wild going into death.”

“Paulus was an undomesticated wild plant,” she continued. “His seed pod was from one of the wild stalks: it burst into the air, and wildly spread those seeds—into the heart of every one of us standing here. Each of us now carries the wild seed. And this is now our job: we are to carry the wild seed forward and grow it again, in all our lives. Paulus gave each of us something wild, something at the edge of ourselves, to carry forward. What will that be? What will you do with it? That is the question.”

-Robin Dreyer

There will be a celebration of Paulus’s life at Penland on July 22. The details are on this page, which may be updated periodically between now and the event.

More about Paulus

Here is a great tribute to Paulus from Debra Frasier and Dan Bailey that was presented at the 2016 Penland benefit auction as part of honoring Paulus as Outstanding Artist Educator.

Here is the trailer for the film To Spring from the Hand. This film, made by Paulus’s long-time friend the late Neil Lawrence, covers many aspects of Paulus’s life and does a beautiful job of presenting his ideas about art and life. The website for the film is gone, but there are some copies of the DVD (also copies of Finding Once’s Way with Clay) available from the Penland supply store (828-765-2359, ext. 1321). Neil also posted four short pieces on YouTube.

Articles published about Paulus after his death:

New York Times

NCECA

The Mitchell News Journal

Paulus’s friend Caverly Morgan, a Buddhist teacher who was an important part of his last days and the events that followed, posted these thoughts.

The Archive of American Art has an extensive oral history interview conducted by Mark Shapiro in 2009.

Garth Clark wrote this short piece about meeting Paulus in 2015.

Here are links to several Paulus videos from the Fetzer Institute

Why We Create

An Artful Approach to Listening