The Penland community lost a bit of its heart and one of its last direct connections to the school’s early days when Bill Ford died on March 21 at age 87. Bill grew up at Penland, and his mother and father played integral parts in the school’s history. For most of his adult life, he lived adjacent to the school in a house he shared with his wife, Suzanne Ford, who was co-director of the Penland Gallery for many years.

In 1993, Robin Dreyer (who is now Penland’s communications manager) wrote an article about Bill for the school’s newsletter, which appears in its entirety below. At that time, Bill had recently recovered from a stroke and had just retired from a long career as a teacher—with all of his summers spent working in various capacities at Penland.

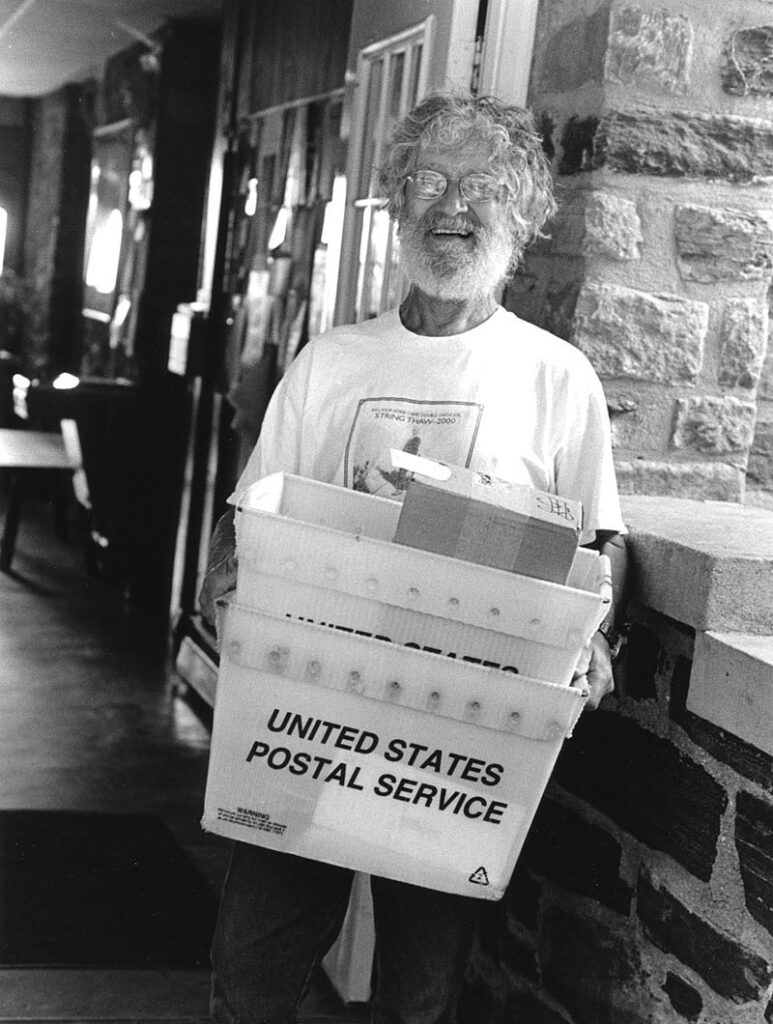

In the 30 years since this story was written, Bill had the daily task of bringing the mail up from the Penland Post Office (Suzanne took over for him a few years ago). He also conducted history-filled tours of the school, built the stone wall behind the Dye Shed, and repaired the stone walls that had been built by his father. And Bill and Suzanne continued to run a small bed and breakfast in their home. People walking by would often see Bill sweeping the driveway or tending to the landscaping.

His mail chore, his frequent walks through the neighborhood, and his cheerful personality made him a familiar and welcome presence at Penland until recent years when old age and dementia began to limit his activities.

Meg Peterson, who was Penland’s teaching artist in the schools for more than 25 years, remembers Bill for his intellectual curiosity and for “his affection for his little part of the world.”

“Bill was deeply rooted here,” she said. “Penland is so transient, and he was a deep and knowing presence who had seen it all and still loved it. He loved the people, he loved the educational community of the public schools, and he loved the woods. It was a remarkable breadth of affection.”

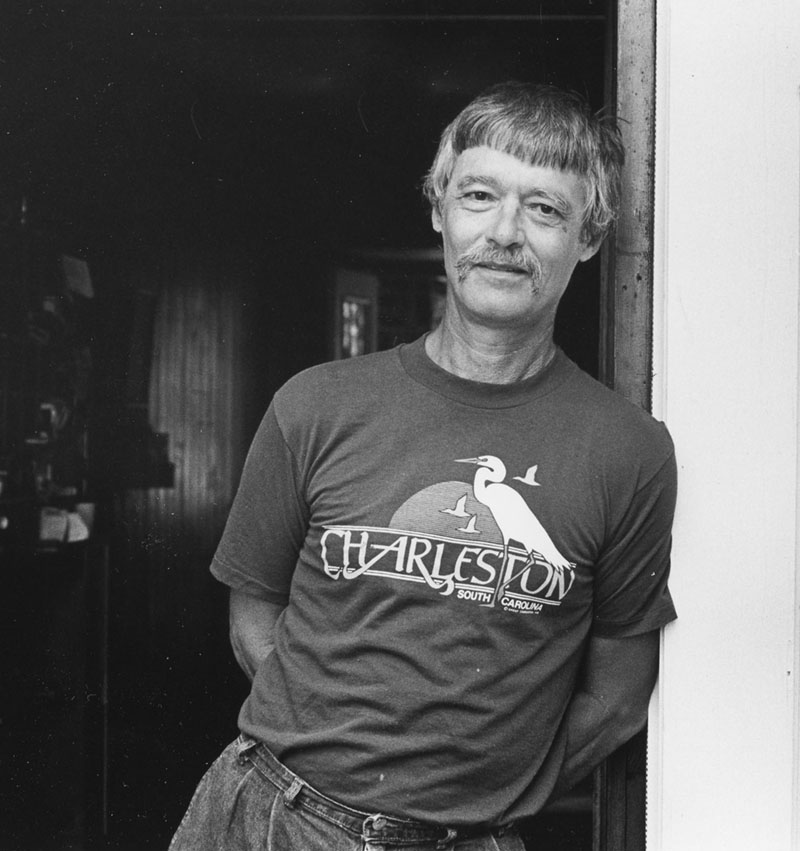

So here is Bill Ford at 57, and at the bottom of the page is a short video of him at 80. We miss him.

Bill Ford: Folk Dancer, Teacher, Penland Institution

from The Penland Line, Fall 1993

“I’m a Willis from Snow Creek, so I understand the mountain people, but I grew up at Penland, which is a world unto itself.”

Bill Ford started working at Penland for ten cents an hour when he was six years old. In the more than 50 summers since then, he has taught enameling and folk dancing, made copper plates for the gift shop, and washed pots in The Pines. He’s currently in charge of mowing the school’s lawns, and, along with his wife, Suzanne, he runs the Chinquapin Inn, in a house that his family used to share with Penland’s founder, Lucy Morgan.

Bill’s roots at Penland School go even deeper than his many summers of work. Lucy Morgan was his godmother, and his grandmother was the first Penland Weaver. (The Penland Weavers was a craft production project that Lucy Morgan started in 1923 before founding the school.) His mother, Bonnie Willis Ford, was, at various times, secretary, registrar, bookkeeper, and interim director. Bill’s father, Howard “Toni” Ford, taught several different crafts, provided technical advice to Lucy Morgan, and once took a small log cabin on a Model T pickup to the Chicago World’s Fair as a sales booth for Penland crafts.

In addition to Penland School, Bill’s other great passions have been folk dancing and teaching. He retired in June [1993] after 30 years as a social studies teacher in the Mitchell County Public Schools, but he originally wanted to be a dancer. He learned folk dancing at Penland as a teenager, when the school used to host weekly community dances. He picked up more folk dances in India, Europe, and Lebanon while his father was stationed overseas with the State Department. At Appalachian State Teacher’s College, he was president of the folk dance club and choreographer for school musicals.

“I took ballet and modern dance when I was 20, and I felt like a pregnant cow the whole time,” he remembers. “All my muscles were set. I realized all of a sudden that this was the end of it. I couldn’t go any further. At that point I settled for teaching, which I enjoy doing, but I guess there’s always been a struggle between the very physical aspect of dance and the intellectual pursuit of teaching.” He did continue with folk dancing, however, and taught it at Penland for more than 20 years.

From Dancing to Social Studies

Bill’s passion for international dance reflects a deeper interest in the cultures of the world, which became the focus of his teaching. “My parents were very inquisitive and broad-minded. From them I got an openness to other people,” he says. Through his teaching, Bill hoped to foster this openness in his students. “I tried to get them to be less ethnocentric, to be more accepting of people who are different.”

His teaching took him in a lot of different directions and sometimes got him into trouble. “I taught everything imaginable in social studies: psychology, sociology, art history, geography, world history, world religion, world culture: anything that could be considered social studies,” he said. “I taught a lot about world religions, which is pretty liberal for this area, I guess, but I felt it was important to teach what other people think. Of course, I used to get into hot water about twice a week!”

He often had to explain to parents that the ideas he was presenting were not his own opinions but were reflections of cultures with a whole different way of looking at things. Despite these misunderstandings, Bill was not one to shy away from a touchy subject. “A lot of teachers absolutely will not talk about anything that’s the least bit controversial, like sex or religion or politics. My position was that if something grew out of a class discussion, if the student was sincere and asked a question, that I would answer the question or tell them where to get the information. I believe that if a student is sufficiently motivated, they are going to learn with you or in spite of you.” He added, however, that he lived in a trailer until the tenure law was passed.

Potwashing With Shakespeare

In between all the years of teaching were the summers at Penland, 20 of which he spent washing pots in the kitchen. “I was interested in the young people that I worked with, and they said it was fun. If I got a pot that was really difficult to scrub, rather than bitch about it, I would recite a Shakespeare sonnet, and when I got through, it was clean, and we would laugh about it.”

One might wonder why a gifted teacher would want to devote so many summers to such unglamorous work. Bill had this answer, “Penland means a great deal to me personally. I grew up here. The Craft House was built from Poplar logs the year I was born. And I want to be useful, in my small way.”

But it isn’t just his personal connection that has kept him coming back. “There is a spirit, a dream that Penland represents,” he says. “People talk about Penland as not being the real world, as being a place where they come and get involved but go away feeling tired but happy and fulfilled. I would hate to see that spirit ever get lost. I’m not afraid of change. It’s necessary; it’s important. The school has to keep up with modern things, but I want to see the best of the past preserved as well.”

In 2015, when Bill was 80, photography student Emma Nash made this short video of a conversation with him, about trees and pinhole cameras, that captures Bill in his later years: playful, observant, a little hard to understand, still curious.

Bill Ford and the Pinhole Camera – Penland, NC from Emma Nash on Vimeo.